Heart Of Darkness Literary Devices

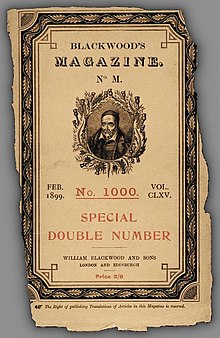

Eye of Darkness was first published every bit a three-role serial story in Blackwood's Magazine. | |

| Writer | Joseph Conrad |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novella |

| Published | 1899 serial; 1902 book |

| Publisher | Blackwood's Mag |

| Preceded by | The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897) |

| Followed by | Lord Jim (1900) |

| Text | Middle of Darkness at Wikisource |

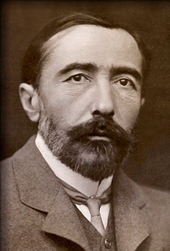

Middle of Darkness (1899) is a novella past Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the crewman Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his consignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The novel is widely regarded as a critique of European colonial dominion in Africa, whilst also examining the themes of power dynamics and morality. Although Conrad does not proper noun the river on which nearly of the narrative takes identify, at the time of writing the Congo Gratuitous State, the location of the large and economically important Congo River, was a individual colony of Belgium's King Leopold Two. Marlow is given a text by Kurtz, an ivory trader working on a trading station far up the river, who has "gone native" and is the object of Marlow's expedition.

Central to Conrad'southward piece of work is the idea that at that place is trivial difference between "civilised people" and "savages." Heart of Darkness implicitly comments on imperialism and racism.[1] The novella's setting provides the frame for Marlow'southward story of his fascination for the prolific ivory trader Kurtz. Conrad draws parallels between London ("the greatest town on earth") and Africa as places of darkness.[two]

Originally issued as a three-part serial story in Blackwood's Magazine to celebrate the thousandth edition of the magazine,[3] Heart of Darkness has been widely republished and translated into many languages. It provided the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola'south 1979 movie Apocalypse At present. In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Centre of Darkness 67th on their list of the 100 best novels in English of the twentieth century.[four]

Limerick and publication [edit]

In 1890, at the age of 32, Conrad was appointed by a Belgian trading company to serve on ane of its steamers. While sailing up the Congo River from one station to another, the captain became ill and Conrad assumed control. He guided the transport up the tributary Lualaba River to the trading company's innermost station, Kindu, in Eastern Congo Free State; Marlow has like experiences to the author.[5]

When Conrad began to write the novella, eight years subsequently returning from Africa, he drew inspiration from his travel journals.[5] He described Eye of Darkness equally "a wild story" of a journalist who becomes manager of a station in the (African) interior and makes himself worshipped by a tribe of natives. The tale was first published equally a three-part serial, in February, March and April 1899, in Blackwood's Magazine (February 1899 was the magazine's 1000th issue: special edition). In 1902 Heart of Darkness was included in the volume Youth: a Narrative, and 2 Other Stories, published on xiii November 1902 past William Blackwood.

The volume consisted of Youth: a Narrative, Heart of Darkness and The End of the Tether in that gild. In 1917, for future editions of the book, Conrad wrote an "Author's Note" where he, after denying any "unity of creative purpose" underlying the collection, discusses each of the three stories and makes light commentary on Marlow, the narrator of the tales within the offset two stories. He said Marlow get-go appeared in Youth.

On 31 May 1902, in a letter of the alphabet to William Blackwood, Conrad remarked,

I call your own kind self to witness ... the last pages of Heart of Darkness where the interview of the man and the girl locks in—as it were—the whole 30000 words of narrative clarification into one suggestive view of a whole stage of life and makes of that story something quite on another airplane than an anecdote of a homo who went mad in the Center of Africa.[half dozen]

In that location have been many proposed sources for the character of the antagonist, Kurtz. Georges-Antoine Klein, an amanuensis who became ill and died aboard Conrad'due south steamer, is proposed by literary critics as a basis for Kurtz.[7] The principal figures involved in the disastrous "rear cavalcade" of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition have also been identified equally likely sources, including column leader Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, slave trader Tippu Tip and the trek leader, Welsh explorer Henry Morton Stanley.[8] [ix] Conrad's biographer Norman Sherry judged that Arthur Hodister (1847–1892), a Belgian solitary just successful trader, who spoke iii Congolese languages and was venerated by Congolese to the bespeak of deification, served as the main model, while afterward scholars accept refuted this hypothesis.[ten] [11] [12] Adam Hochschild, in Rex Leopold's Ghost, believes that the Belgian soldier Léon Rom influenced the graphic symbol.[13] Peter Firchow mentions the possibility that Kurtz is a composite, modelled on diverse figures nowadays in the Congo Free State at the time as well as on Conrad's imagining of what they might take had in common.[14]

A corrective impulse to impose ane's rule characterizes Kurtz's writings which were discovered by Marlow during his journeying, where he rants on behalf of the so-called "International Lodge for the Suppression of Savage Community" about his supposedly altruistic and sentimental reasons to civilise the "savages"; one document ends with a dark declaration to "Exterminate all the brutes!".[15] The "International Society for the Suppression of Fell Customs" is interpreted as a sarcastic reference to one of the participants at the Berlin Conference, the International Clan of the Congo (also called "International Congo Society").[16] [17] The predecessor to this organisation was the "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa".

Summary [edit]

Charles Marlow tells his friends the story of how he became helm of a river steamboat for an ivory trading visitor. As a child, Marlow was fascinated by "the blank spaces" on maps, specially Africa. The image of a river on the map particularly fascinated Marlow.

In a flashback, Marlow makes his way to Africa, taking passage on a steamer. He travels 30 mi (50 km) up the river where his company'due south station is. Work on a railway is going on. Marlow explores a narrow ravine, and is horrified to find himself in a identify full of critically ill Africans who worked on the railroad and are now dying. Marlow must wait for 10 days in the company's devastated Outer Station. Marlow meets the company'southward chief accountant, who tells him of a Mr. Kurtz, who is in charge of a very important trading mail, and is described as a respected showtime-class amanuensis. The accountant predicts that Kurtz will get in.

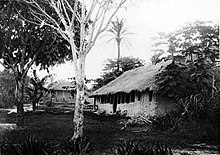

Belgian river station on the Congo River, 1889

Marlow departs with lx men to travel to the Primal Station, where the steamboat is based that he volition command. At the station, he learns that his steamboat has been wrecked in an accident. The full general director informs Marlow that he could not wait for Marlow to arrive, and tells him of a rumour that Kurtz is ill. Marlow fishes his boat out of the river and spends months repairing it. Delayed past the lack of tools and replacement parts, Marlow is frustrated past the time it takes to perform the repairs. He learns that Kurtz is resented, non admired, by the manager. Once underway, the journey to Kurtz's station takes two months.

The Roi des Belges ("King of the Belgians"—French), the Belgian riverboat Conrad allowable on the upper Congo, 1889

The journey pauses for the night nearly viii miles (13 km) below the Inner Station. In the morning the boat is enveloped by a thick fog. The steamboat is afterwards attacked past a avalanche of arrows, and the helmsman is killed. Marlow sounds the steam whistle repeatedly, frightening the attackers away.

After landing at Kurtz's station, a man boards the steamboat: a Russian wanderer who strayed into Kurtz'southward military camp. Marlow learns that the natives worship Kurtz and that he has been very ill. The Russian tells of how Kurtz opened his mind and admires Kurtz even for his ability and his willingness to use it. Marlow suspects that Kurtz has gone mad.

Marlow observes the station and sees a row of posts topped with the severed heads of natives. Effectually the corner of the house, Kurtz appears with supporters who carry him as a ghost-like effigy on a stretcher. The surface area fills with natives prepare for boxing, but Kurtz shouts something and they retreat. His entourage carries Kurtz to the steamer and lay him in a cabin. The managing director tells Marlow that Kurtz has harmed the company'due south business in the region because his methods are "unsound". The Russian reveals that Kurtz believes the company wants to impale him, and Marlow confirms that hangings were discussed.

Arthur Hodister (1847–1892), who Conrad's biographer Norman Sherry has argued served as one of the sources of inspiration for Kurtz

After midnight, Kurtz returns to shore. Marlow finds Kurtz crawling back to the station house. Marlow threatens to harm Kurtz if he raises an alarm, merely Kurtz but laments that he did not accomplish more. The adjacent 24-hour interval they set to journeying back downwards the river.

Kurtz's wellness worsens during the trip. The steamboat breaks downwardly, and while stopped for repairs, Kurtz gives Marlow a packet of papers, including his commissioned report and a photograph, telling him to keep them from the director. When Marlow side by side speaks with him, Kurtz is near death; Marlow hears him weakly whisper, "The horror! The horror!" A curt while later, the manager's boy announces to the crew that Kurtz has died. The next 24-hour interval Marlow pays piddling attending to Kurtz'southward pilgrims as they bury "something" in a muddy hole.

Returning to Europe, Marlow is embittered and cynical of the "civilised" world. Several callers come to recall the papers Kurtz entrusted to him, but Marlow withholds them or offers papers he knows they have no interest in. He gives Kurtz's report to a announcer, for publication if he sees fit. Marlow is left with some personal messages and a photo of Kurtz'southward fiancée. When Marlow visits her, she is deep in mourning although it has been more than a year since Kurtz's death. She presses Marlow for information, asking him to repeat Kurtz's final words. Marlow tells her that Kurtz's final give-and-take was her proper name.

Critical reception [edit]

The novella was not a big success during Conrad's life.[18] When it was published as a unmarried volume in 1902 with ii novellas, "Youth" and "The End of the Tether", it received the least commentary from critics.[18] F. R. Leavis referred to Eye of Darkness as a "minor piece of work" and criticised its "adjectival insistence upon inexpressible and incomprehensible mystery".[19] Conrad did non consider it to be specially notable;[18] but by the 1960s it was a standard assignment in many college and high schoolhouse English language courses.[twenty]

Literary critic Harold Flower wrote that Heart of Darkness had been analysed more than whatever other piece of work of literature that is studied in universities and colleges, which he attributed to Conrad'due south "unique propensity for ambiguity".[21] In King Leopold's Ghost (1998), Adam Hochschild wrote that literary scholars have fabricated also much of the psychological aspects of Center of Darkness, while paying scant attention to Conrad's accurate recounting of the horror arising from the methods and effects of colonialism in the Congo Free Land. "Heart of Darkness is experience ... pushed a little (and only very fiddling) across the actual facts of the case".[22] Other critiques include Hugh Curtler's Achebe on Conrad: Racism and Greatness in Heart of Darkness (1997).[23] The French philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe called Middle of Darkness "1 of the greatest texts of Western literature" and used Conrad's tale for a reflection on "The Horror of the West".[24]

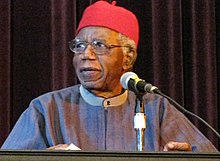

Chinua Achebe's 1975 lecture on the book sparked decades of argue.

Middle of Darkness is criticised in postcolonial studies, peculiarly by Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe.[25] [26] In his 1975 public lecture "An Epitome of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness", Achebe described Conrad's novella as "an offensive and deplorable volume" that de-humanised Africans.[27] Achebe argued that Conrad, "blinkered ... with xenophobia", incorrectly depicted Africa as the antithesis of Europe and civilisation, ignoring the artistic accomplishments of the Fang people who lived in the Congo River basin at the time of the volume'south publication. He argued that the book promoted and continues to promote a prejudiced epitome of Africa that "depersonalises a portion of the human race" and ended that it should non be considered a great work of art.[25] [28]

Achebe's critics argue that he fails to distinguish Marlow's view from Conrad'due south, which results in very impuissant interpretations of the novella.[29] In their view, Conrad portrays Africans sympathetically and their plight tragically, and refers sarcastically to, and condemns outright, the supposedly noble aims of European colonists, thereby demonstrating his skepticism about the moral superiority of European men.[xxx] Ending a passage that describes the status of chained, emaciated slaves, Marlow remarks: "After all, I also was a part of the great cause of these high and just proceedings." Some observers assert that Conrad, whose native country had been conquered past imperial powers, empathised past default with other subjugated peoples.[31] Jeffrey Meyers notes that Conrad, similar his associate Roger Casement, "was one of the kickoff men to question the Western notion of progress, a dominant idea in Europe from the Renaissance to the Neat War, to set on the hypocritical justification of colonialism and to reveal... the cruel degradation of the white man in Africa."[32] : 100–01 Likewise, E.D. Morel, who led international opposition to King Leopold Ii's dominion in the Congo, saw Conrad's Heart of Darkness every bit a condemnation of colonial brutality and referred to the novella as "the almost powerful thing written on the discipline."[33]

Author and anti-slavery pacifist Due east. D. Morel (1873–1924) considered the novella was "the almost powerful thing written on the bailiwick."

Conrad scholar Peter Firchow writes that "nowhere in the novel does Conrad or whatsoever of his narrators, personified or otherwise, claim superiority on the part of Europeans on the grounds of alleged genetic or biological divergence". If Conrad or his novel is racist, information technology is only in a weak sense, since Heart of Darkness acknowledges racial distinctions "just does not suggest an essential superiority" of whatsoever grouping.[34] [35] Achebe's reading of Heart of Darkness tin be (and has been) challenged past a reading of Conrad's other African story, "An Outpost of Progress", which has an omniscient narrator, rather than the embodied narrator, Marlow. Masood Ashraf Raja has suggested that Conrad's positive representation of Muslims in his Malay novels complicates these charges of racism.[36]

In 2003, Motswana scholar Peter Mwikisa concluded the book was "the keen lost opportunity to depict dialogue between Africa and Europe".[37] Zimbabwean scholar Rino Zhuwarara, still, broadly agreed with Achebe, though considered it important to exist "sensitised to how peoples of other nations perceive Africa".[38] The novelist Caryl Phillips stated in 2003 that: "Achebe is correct; to the African reader the price of Conrad'due south eloquent denunciation of colonisation is the recycling of racist notions of the 'night' continent and her people. Those of usa who are not from Africa may exist prepared to pay this price, but this price is far too loftier for Achebe".[39]

In his 1983 criticism, the British academic Cedric Watts criticizes the insinuation in Achebe's critique—the premise that only black people may accurately analyse and appraise the novella, as well as mentioning that Achebe's critique falls into self-contradictory arguments regarding Conrad's writing style, both praising and denouncing information technology at times.[40] Stan Galloway writes, in a comparison of Center of Darkness with Jungle Tales of Tarzan, "The inhabitants [of both works], whether antagonists or compatriots, were clearly imaginary and meant to stand for a detail fictive nothing and not a particular African people".[41] More recent critics accept stressed that the "continuities" between Conrad and Achebe are profound and that a grade of "postcolonial mimesis" ties the two authors.[42]

Adaptations and influences [edit]

Radio and stage [edit]

Orson Welles adapted and starred in Centre of Darkness in a CBS Radio circulate on 6 November 1938 as function of his series, The Mercury Theatre on the Air. In 1939, Welles adapted the story for his starting time motion-picture show for RKO Pictures,[43] writing a screenplay with John Houseman. The story was adapted to focus on the rise of a fascist dictator.[43] Welles intended to play Marlow and Kurtz[43] and it was to be entirely filmed as a POV from Marlow's eyes. Welles even filmed a short presentation picture illustrating his intent. It is reportedly lost. The film'south prologue to be read by Welles said "You aren't going to see this picture - this picture show is going to happen to you lot."[43] The project was never realised; one reason given was the loss of European markets after the outbreak of World State of war II. Welles nonetheless hoped to produce the film when he presented another radio adaptation of the story as his first plan every bit producer-star of the CBS radio series This Is My Best. Welles scholar Bret Wood called the broadcast of 13 March 1945, "the closest representation of the moving-picture show Welles might take fabricated, bedridden, of grade, by the absence of the story's visual elements (which were so meticulously designed) and the half-hour length of the circulate."[44] : 95, 153–156, 136–137

In 1991, Australian author/playwright Larry Buttrose wrote and staged a theatrical adaptation titled Kurtz with the Crossroads Theatre Company, Sydney.[45] The play was announced to be circulate as a radio play to Australian radio audiences in August 2011 by the Vision Australia Radio Network,[46] and as well past the RPH – Radio Print Handicapped Network beyond Australia.

In 2011, composer Tarik O'Regan and librettist Tom Phillips adapted an opera of the same name, which premiered at the Linbury Theatre of the Royal Opera House in London.[47] A suite for orchestra and narrator was subsequently extrapolated from it.[48]

In 2015, an adaption of Welles' screenplay by Jamie Lloyd and Laurence Bowen aired on BBC Radio iv.[49] The production starred James McAvoy equally Marlow.

Picture show and television [edit]

The CBS television anthology Playhouse 90 aired a loose 90-minute adaptation in 1958, Eye of Darkness (Playhouse 90). This version, written by Stewart Stern, uses the encounter between Marlow (Roddy McDowall) and Kurtz (Boris Karloff) as its concluding deed, and adds a backstory in which Marlow had been Kurtz'due south adopted son. The cast includes Inga Swenson and Eartha Kitt.[50]

Perhaps the all-time known adaptation is Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 film Apocalypse Now, based on the screenplay past John Milius, which moves the story from the Congo to Vietnam and Cambodia during the Vietnam War.[51] In Apocalypse Now, Martin Sheen stars as Captain Benjamin L. Willard, a United states Ground forces Helm assigned to "terminate the control" of Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, played past Marlon Brando. A film documenting the production, titled Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker'south Apocalypse, showed some of the difficulties which managing director Coppola faced making the flick, which resembled some of the novella'south themes.

On 13 March 1993, TNT aired a new version of the story, directed past Nicolas Roeg, starring Tim Roth as Marlow and John Malkovich as Kurtz.[52]

James Grey'due south 2019 science fiction film Advertisement Astra is loosely inspired by the events of the novel. It features Brad Pitt as an astronaut travelling to the border of the Solar System to confront and potentially kill his father (Tommy Lee Jones), who has gone rogue.[53]

In 2020, African Apocalypse, a documentary film directed and produced by Rob Lemkin and featuring Femi Nylander portrays a journey from Oxford, England to Niger on the trail of a colonial killer called Captain Paul Voulet. Voulet's descent into barbarity mirrors that of Kurtz in Conrad'due south Heart of Darkness. Nylander discovers Voulet's massacres happened at exactly the same time that Conrad wrote his book in 1899. It was broadcast by the BBC in May 2021 as an episode of the Arena documentary series.[54]

In 2022, Mr. Harrigan's Phone, In Stephen Male monarch's Netflix horror film, the discipline of the plot, a child who reads classic English books to an onetime American billionaire man of affairs, 1 twenty-four hour period reads a passage from Heart of Darkness. The old human, Mr. Harrigan, then asks the kid if he understood what he read, to which the kid responds that he thinks he does. The one-time man seems unconvinced and satisfied and chop-chop changes the subject, every bit he feels the child is either not ready, or should be protected from understanding the meaning of the ideas delivered from that book. Later in the picture, the boy turned young adult, recalls the passage he read, as he ponders a horrifying truth he just learned. [55]

Video games [edit]

The video game Far Cry 2, released on 21 October 2008, is a loose modernised adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The histrion assumes the role of a mercenary operating in Africa whose chore it is to kill an arms dealer, the elusive "Jackal". The last expanse of the game is chosen "The Heart of Darkness".[56] [57] [58]

Spec Ops: The Line, released on 26 June 2012, is a straight modernised accommodation of Heart of Darkness. The player assumes the role of Delta Strength operator Captain Martin Walker as he and his squad search Dubai for survivors in the aftermath of catastrophic sandstorms that left the city without contact to the outside world. The character John Konrad, who replaces the graphic symbol Kurtz, is a reference to Joseph Conrad.[59]

Victoria II, a k strategy game produced by Paradox Interactive, launched an expansion pack titled "Heart of Darkness" on sixteen April 2013, which revamped the game's colonial system, and naval warfare.[lx]

Earth of Warcraft 's seventh expansion, Boxing for Azeroth, has a dark, swampy zone named Nazmir that makes many references to both Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now. Examples include the sub zone "Heart of Darkness" and a quest of the same name that mentions a character named "Captain Conrad", amongst others.[61] [62]

Literature [edit]

T. S. Eliot's 1925 poem The Hollow Men quotes, as its showtime epigraph, a line from Heart of Darkness: "Mistah Kurtz – he dead."[63] Eliot had planned to use a quotation from the climax of the tale as the epigraph for The Waste State, but Ezra Pound brash confronting it.[64] Eliot said of the quote that "it is much the most appropriate I tin notice, and somewhat elucidative."[65] Biographer Peter Ackroyd suggested that the passage inspired or at least anticipated the central theme of the poem.[66]

Chinua Achebe'south 1958 novel Things Fall Autonomously is Achebe's response to what he saw as Conrad's portrayal of Africa and Africans equally symbols-- "the antithesis of Europe and therefore civilization".[67] Achebe ready out to write a novel about Africa and Africans by an African. In Things Fall Apart we see the furnishings of colonialism and Christian missionary endeavors on an Igbo community in West Africa through the eyes of that community's West African protagonists.

The novel Hearts of Darkness by Paul Lawrence moves the events of the novel to England in the mid-17th century. Marlow's journeying into the jungle becomes a journey by the narrator, Harry Lytle, and his friend Davy Dowling out of London and towards Shyam, a plague-stricken town that has descended into cruelty and barbarism, loosely modelled on existent-life Eyam. While Marlow must return to civilisation with Kurtz, Lytle and Dowling are searching for the spy James Josselin. Like Kurtz, Josselin'south reputation is immense and the protagonists are well-acquainted with his accomplishments by the fourth dimension they run into him.[68]

Poet Yedda Morrison's 2012 book Darkness erases Conrad's novella, "whiting out" his text so that but images of the natural world remain.[69]

James Reich's Mistah Kurtz! A Prelude to Middle of Darkness presents the early life of Kurtz, his appointment to his station in the Congo and his messianic disintegration in a novel that dovetails with the conclusion of Conrad's novella. Reich'due south novel is premised upon the papers Kurtz leaves to Marlow at the end of Eye of Darkness.[70]

In Josef Škvorecký's 1984 novel The Engineer of Human being Souls, Kurtz is seen as the epitome of exterminatory colonialism and, in that location and elsewhere, Škvorecký emphasises the importance of Conrad's business with Russian imperialism in Eastern Europe.[71]

Timothy Findley's 1993 novel Headhunter is an all-encompassing adaptation that reimagines Kurtz and Marlow as psychiatrists in Toronto. The novel begins: "On a winter's twenty-four hour period, while a blizzard raged through the streets of Toronto, Lilah Kemp inadvertently ready Kurtz free from page 92 of Heart of Darkness."[72] [73]

Another literary work with an acknowledged debt to Eye of Darkness is Wilson Harris' 1960 postcolonial novel Palace of the Peacock.[74] [75] [76]

J. G. Ballard'due south 1962 climate fiction novel The Drowned World includes many similarities to Conrad's novella. However, Ballard said he had read nothing past Conrad before writing the novel, prompting literary critic Robert S. Lehman to remark that "the novel'due south allusion to Conrad works nicely, fifty-fifty if it is not really an allusion to Conrad".[77] [78]

Robert Silverberg's 1970 novel Down to the Globe uses themes and characters based on Center of Darkness assault the alien globe of Belzagor.[79]

Notes [edit]

- ^ The Norton Anthology, 7th edition, (2000), p. 1957.

- ^ Chinua Achebe "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad'south Heart of Darkness" in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. two (seventh edition) (2000), p. 2036.

- ^ National Library of Scotland: Blackwoods magazine exhibition. In Blackwood's, the story is titled "The Middle of Darkness" only when published every bit a separate volume "The" was dropped from the title.

- ^ 100 All-time Archived 7 February 2010 at the Wayback Automobile, Modern Library'due south website. Retrieved 12 Jan 2010.

- ^ a b Bloom 2009, p. 15

- ^ Karl & Davies 1986, p. 417

- ^ Karl, F.R. (1968). "Introduction to the trip the light fantastic macabre: Conrad's Heart of Darkness". Mod Fiction Studies. 14 (ii): 143–156.

- ^ Bloom 2009, p. xvi

- ^ Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold'due south Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa . New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 98, 145. ISBN978-0-395-75924-0 – via Internet Annal.

- ^ Sherry, Norman (1971). Conrad's Western Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. p. 95.

- ^ Coosemans, M. (1948). "Hodister, Arthur". Biographie Coloniale Belge. I: 514–518.

- ^ Firchow, Peter (2015). Envisioning Africa: Racism and Imperialism in Conrad's Middle of Darkness. Academy Printing of Kentucky. pp. 65–68.

- ^ Ankomah, Baffour (October 1999). "The Butcher of Congo". New African.

- ^ Firchow, Peter (2015). Envisioning Africa: Racism and Imperialism in Conrad'southward Center of Darkness. University of Kentucky Press. pp. 67–68.

- ^ Shah, Sonal (26 April 2018). "A Photographer Takes the Bull past the Horns in His Jallikattu Series". Vice.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Historical Context: Middle of Darkness." EXPLORING Novels, Online Edition. Gale, 2003. Discovering Collection. (subscription required)

- ^ Stengers, Jean. "Sur l'aventure congolaise de Joseph Conrad". In Quaghebeur, Thousand. And van Balberghe, eastward. (Eds.), Papier Blanc, Encre Noire: Cent Ans de Culture Francophone en Afrique Centrale (Zaïre, Rwanda et Burundi). 2 Vols. Pp. 15-34. Brussels: Labor. 1.

- ^ a b c Moore 2004, p. 4

- ^ Moore 2004, p. 5

- ^ "13.02.01: Moving Across "Huh?": Ambivalence in Heart of Darkness". Archived from the original on 21 November 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2009, p. 17

- ^ Hochschild 1999, p. 143

- ^ Curtler, Hugh (March 1997). "Achebe on Conrad: Racism and Greatness in Heart of Darkness". Conradiana. 29 (1): xxx–xl.

- ^ Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe. "The Horror of the W". Bloomsbury. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b Podgorski, Daniel (6 October 2015). "A Controversy Worth Teaching: Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and the Ethics of Stature". The Gemsbok. Your Tuesday Tome. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved nineteen Feb 2016.

- ^ "Chinua Achebe Biography". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Watts, Cedric (1983). "'A Bloody Racist': About Achebe's View of Conrad". The Yearbook of English Studies. xiii: 196–209. doi:10.2307/3508121. JSTOR 3508121.

- ^ Achebe, Chinua (1978). "An Image of Africa". Research in African Literatures. 9 (1): ane–xv. JSTOR 3818468.

- ^ Lackey, Michael (Winter 2005). "The Moral Weather for Genocide in Joseph Conrad's "Centre of Darkness"". College Literature. 32 (one): twenty–41. doi:10.1353/lit.2005.0010. JSTOR 25115244.

- ^ Watts, Cedric (1983). "'A Encarmine Racist': About Achebe's View of Conrad". The Yearbook of English Studies. 13: 196–209. doi:x.2307/3508121. JSTOR 3508121.

- ^ Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness, Book I . Archived from the original on 21 Nov 2021.

- ^ Jeffrey Meyers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, 1991.

- ^ Morel, Due east.D. (1968). History of the Congo Reform Movement. Ed. William Roger Louis and Jean Stengers. London: Oxford Upwardly. pp. 205, due north.

- ^ Firchow, Peter (2000). Envisioning Africa: Racism and Imperialism in Conrad'south Middle of Darkness. Academy Press of Kentucky. pp. ten–11. ISBN978-0-8131-2128-iv.

- ^ Lackey, Michael (Summer 2003). "Conrad Scholarship Under New-Millennium Western Eyes". Periodical of Modern Literature. 26 (iii/four): 144. doi:10.1353/jml.2004.0030. S2CID 162347476. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021.

- ^ Raja, Masood (2007). "Joseph Conrad: Question of Racism and the Representation of Muslims in his Malayan Works". Postcolonial Text. 3 (four): xiii. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021.

- ^ Mwikisa, Peter. "Conrad's Image of Africa: Recovering African Voices in Center of Darkness. Mots Pluriels 13 (April 2000): twenty–28.

- ^ Moore 2004, p. 6

- ^ Phillips, Caryl (22 February 2003). "Out of Africa". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved thirty Nov 2014.

- ^ Watts, Cedric (1983). "'A Bloody Racist': Virtually Achebe'southward View of Conrad". The Yearbook of English Studies. thirteen: 196–209. doi:10.2307/3508121. JSTOR 3508121.

- ^ Galloway, Stan. The Teenage Tarzan: A Literary Analysis of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Jungle Tales of Tarzan. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010. p. 112.

- ^ Lawtoo, Nidesh (2013). "A Motion-picture show of Africa: Frenzy, Counternarrative, Mimesis" (PDF). Modern Fiction Studies. 59 (1): 26–52. doi:x.1353/mfs.2013.0000. S2CID 161325915.

- ^ a b c d Hitchens, Gordon (13 June 1979). "Orson Welles Prior Interest In Conrad's 'Center of Darkness'". Variety. p. 24.

- ^ Wood, Bret, Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1990 ISBN 0-313-26538-0

- ^ "Larry Buttrose". doollee.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Vision Australia". Visionaustralia.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Majestic Opera House Page for Heart of Darkness Archived xx October 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Tarik O'Regan and Tom Phillips

- ^ Suite from Heart of Darkness first London performance, Cadogan Hall, archived from the original on 21 November 2021, retrieved 17 June 2015

- ^ "Orson Welles' Heart of Darkness, Unmade Movies, Drama – BBC Radio 4". BBC. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved three November 2015.

- ^ Bandage and credits are available at "The Internet Movie Database". Retrieved 2 December 2010. A full recording can be viewed onsite by members of the public upon request at The Paley Center for Media (formerly the Museum of Television & Radio) in New York City and Los Angeles.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (iii Baronial 2001). "Aching Heart of Darkness". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Tucker, Ken. Eye of Darkness. Amusement Weekly, 11 March 1994. Retrieved four April 2010.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam (10 April 2017). "James Gray Says His Sci-Fi Movie 'Ad Astra' Starts Filming This Summer with Brad Pitt". Collider. Complex Media Inc. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Nwokorie, Lynn (16 Oct 2020). "African Apocalypse". British Pic Establish . Retrieved 12 Dec 2021.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (three October 2022). "Mr. Harrigan'southward Phone". Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ Mikel Reparaz (30 July 2007). "The Darkness". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on v November 2012.

- ^ "Africa Wins Again: Far Cry 2's literary approach to narrative". Infovore.org. Archived from the original on 5 Nov 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Far Cry 2 – Jorge Albor – ETC Press". Cmu.edu. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Spec Ops: The Line preview – middle of darkness". Metro. 10 January 2012. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Victoria 2: Heart of Darkness – Paradox Interactive". Paradoxplaza.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Centre of Darkness (Nazmir)". Wowpedia . Retrieved sixteen December 2020.

- ^ "Heart of Darkness". Wowhead. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Ebury, Katherine (2012). "'In this valley of dying stars': Eliot's Cosmology. Journal of Modern Literature], vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 139-57.

- ^ Pound, Ezra (1950). The Letters of Ezra Pound. London: Faber and Faber. p. 234.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1988). The Messages of T.S. Eliot: 1898-1922. London: Faber and Faber. p. 504. ISBN0571136214.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (1984). T.Due south, Eliot. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 118. ISBN0671530437.

- ^ Achebe, Chinua. "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad'southward "Heart of Darkness"". Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Hearts of Darkness". Allisonandbusby.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Morrison, Yedda. "Yedda Morrison". Yeddamorrison.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Hurley, Brian (14 March 2016). "Q&A with James Reich, Author of Mistah Kurtz". Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Škvorecký, Josef (1984). "Why the Harlequin? On Conrad'south Centre of Darkness." Cross Currents: A Yearbook of Central European Culture, vol. iii, pp. 259-264.

- ^ Findley, Timothy (1993). Headhunter. Toronto: HarperCollins.

- ^ Brydon, Diana (1999). "Intertextuality in Timothy Findley's Headhunter". Journal of Canadian Studies. 33 (4): 53–62. doi:ten.3138/jcs.33.4.53. S2CID 140336153.

- ^ Harris, Wilson (1960). Palace of the Peacock. London: Faber & Faber.

- ^ Harris, Wilson (1981). "The Frontier on Which Middle of Darkness Stands." Inquiry in African Literatures, vol. 12, no. one, pp. 86-93.

- ^ Carr, Robert (1995). "The New Man in the Jungle: Chaos, Community, and the Margins of the Nation-State." Callaloo, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 133-56.

- ^ Ballard, J.G. (1962). The Drowned World. New York: Berkley.

- ^ Lehman, Robert Southward. (2018). "Back to the Future: Late Modernism in J.K. Ballard's The Drowned Earth. Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 41, no. iv, p. 167.

- ^ "The Humanoids Weblog, Interview: Robert Silverberg". humanoids.com. Archived from the original on 21 Nov 2021. Retrieved nine July 2021.

References [edit]

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (2009). Joseph Conrad's Centre of Darkness. Infobase Publishing. ISBN978-1438117102.

- Hochschild, Adam (October 1999). "Chapter nine: Meeting Mr. Kurtz". King Leopold'southward Ghost. Mariner Books. pp. 140–149. ISBN978-0-618-00190-three.

- Karl, Frederick R.; Davies, Laurence, eds. (1986). The Nerveless Letters of Joseph Conrad – Volume 2: 1898 – 1902. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-25748-0.

- Moore, Factor M., ed. (2004). Joseph Conrad'southward Heart of Darkness: A Casebook. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0195159967.

- Murfin, Ross C., ed. (1989). Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness. A Case Report in Contemporary Criticism . St. Martin's Printing. ISBN978-0-312-00761-4.

- Sherry, Norman (30 June 1980). Conrad's Western World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-29808-7.

Farther reading [edit]

- Farn, Regelind Colonial and Postcolonial Rewritings of "Heart of Darkness" – A Century of Dialogue with Joseph Conrad (2004). A dissertation.

- Firchow, P. Envisioning Africa: Racism and Imperialism in Conrad'south 'Heart of Darkness (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000).

- Lawtoo, Nidesh, ed. Conrad'due south Center of Darkness and Contemporary Thought: Revisiting the Horror with Lacoue-Labarthe (London: Bloomsbury, 2012).

- Parry, Benita Conrad and Imperialism (London: Macmillan, 1983).

- Said, Edward W. Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1966) [no ISBN].

- Watts, Cedric Conrad's 'Middle of Darkness': A Critical and Contextual Discussion (Milan: Mursia International, 1977).

External links [edit]

![]()

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Heart of Darkness at Standard Ebooks

- Heart of Darkness at Projection Gutenberg

- Heart of Darkness on In Our Fourth dimension at the BBC

- Downloadable audio book of Heart of Darkness by LoudLit.org

-

Heart of Darkness public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Heart of Darkness public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre on the Air sound books, also of Heart of Darkness

- Orson Welles Mercury Theatre 1938, also of Centre of Darkness

- This Is My All-time — Heart of Darkness (13 March 1945) at the Paley Center for Media

Heart Of Darkness Literary Devices,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heart_of_darkness

Posted by: andersonates1978.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Heart Of Darkness Literary Devices"

Post a Comment